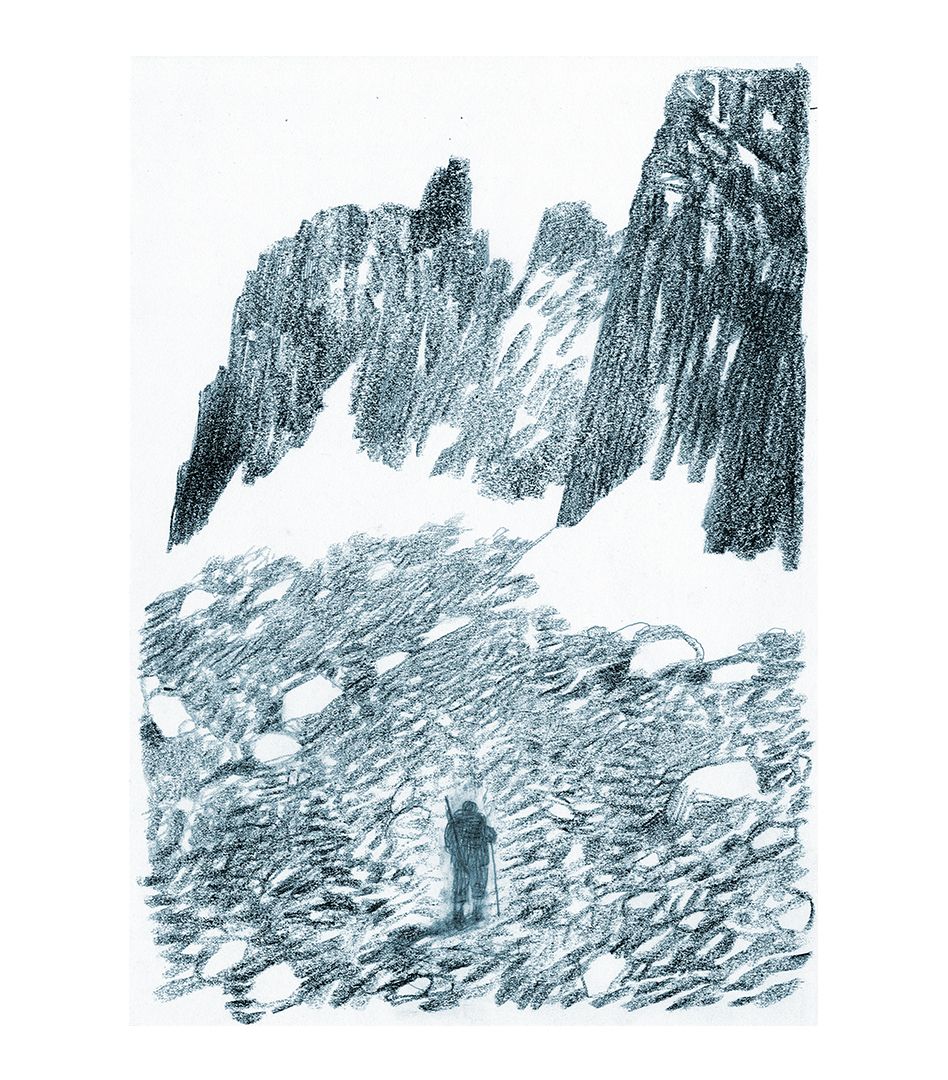

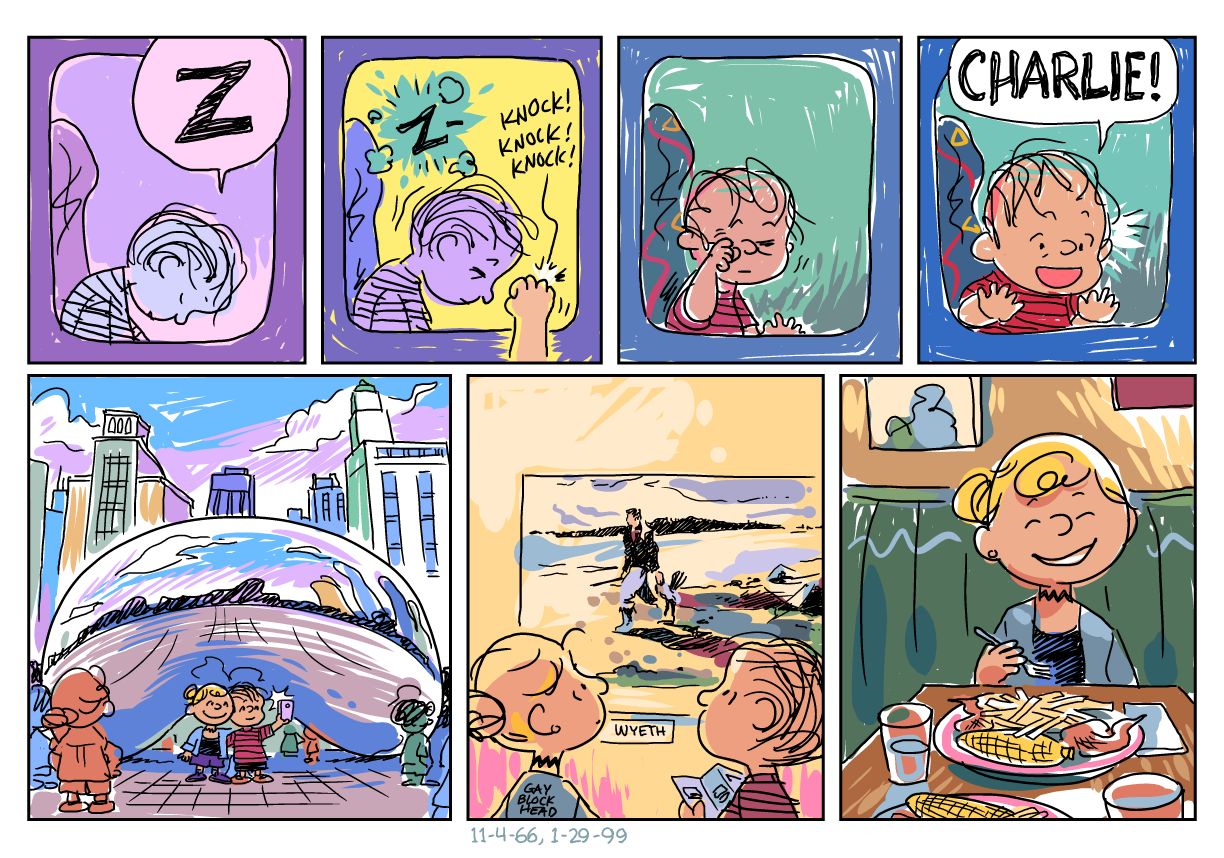

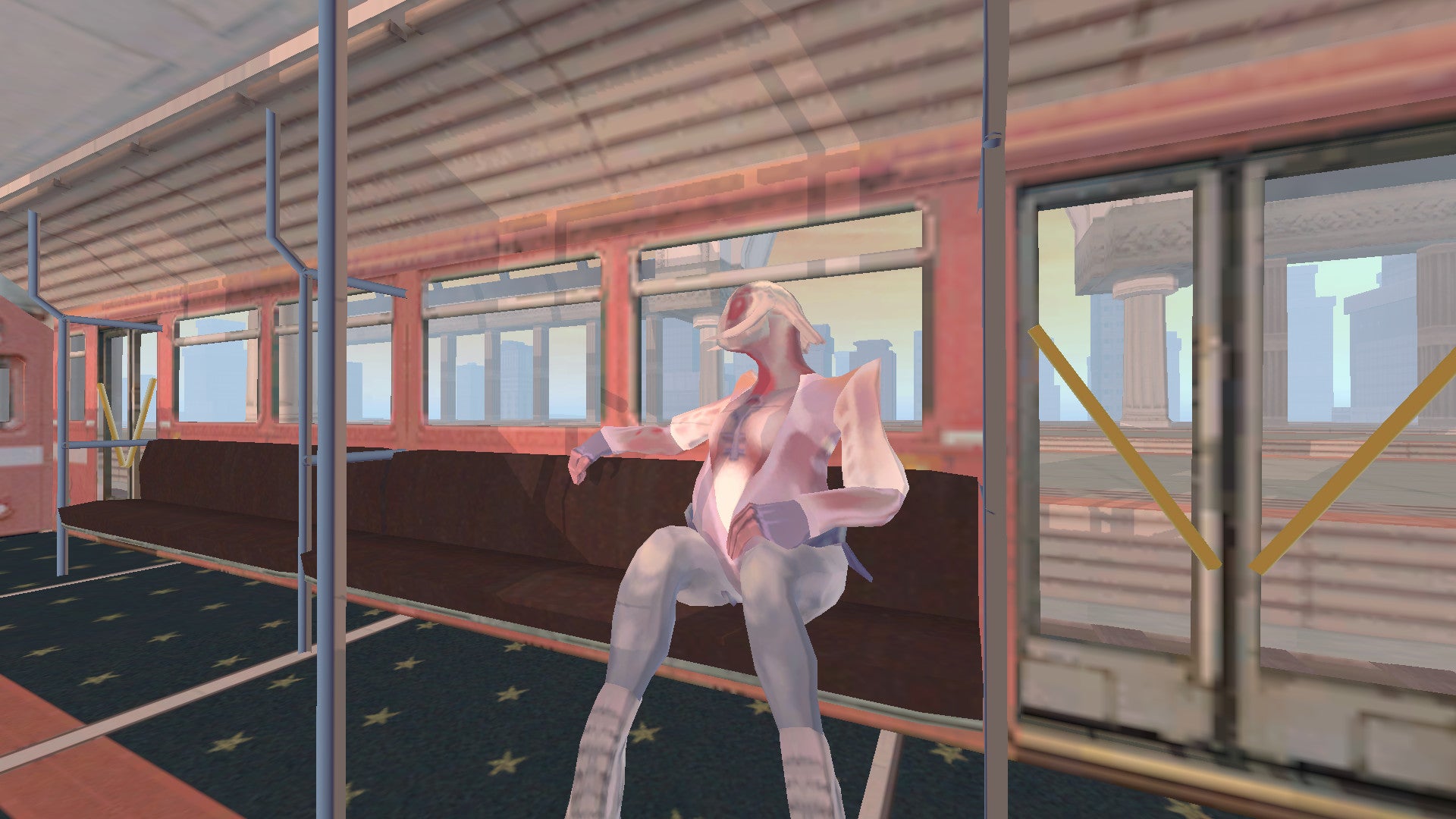

When the player begins Analgesic’s newest game Sephonie - part 3D platformer, part deep emotional story - three Taiwanese biologists make their way onto the titular island to explore. As the Steam page puts it: “Amy Lim, Taiwanese-American and bold leader, hails from the midwestern USA town of Bloomington. Riyou Hayashi, an analytically-minded Japanese-Taiwanese researcher, calls the bustling Tokyo his home. And Ing-wen Lin, a kind and considerate Taiwanese scientist, lives in Taipei.” For Analgesic’s blog, the duo wrote a post reflecting on the fourth anniversary of Even The Ocean. Han-Tani called the work, their lowest-selling effort, “a beautiful, unique, and unparalleled game,” and he’s absolutely right. In this post Han-Tani looks back at his previous efforts in just the way I wish all artists could: with pride, grace, and a warm, scientific eye for criticism. The first thing that may strike players about Analgesic’s mixed-3D-and-2D outings Anodyne 2 and Sephonie are the calm, confident, aesthetics, both musically and visually. Comparisons get drawn to the graphics of 90s consoles such as the original Sony PlayStation, the Nintendo 64, and the SEGA Dreamcast. I wanted to ask Kittaka, who is Analgesic’s visual designer and illustrator (and, for disclosure, a friend of mine), how she crafted these lovely pastel and earth-toned worlds. “I’m certainly informed by many old and contemporary lo-fi games,” Kittaka tells me. “Although I guess I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about what is old or new, restricted or unrestricted. One of the biggest influences that I must acknowledge on Sephonie’s art style is the contemporary Italian illustrator Andrea Serio.” “Sephonie’s parkour style wallrun and vaulting mechanics mean that the vast majority of visible shapes have significant gameplay meaning,” Kittaka continues. “I wanted to create the environments out of large, legible forms, because too many small or irregular shapes would strangle the physical possibilities or create uncomfortable ambiguities. Serio’s beautiful work helped me understand how to shift between organic and man-made shapes within a persistent large, shapey style.” Kittaka’s playful use of her own momentary term - shapey - reminded me of the humour she often employs in many media: in games; in poems such as Boys in which she writes, “I want to super smash boys”; in her romantic, nostalgic, complex comic Good Ol’ Charlie B; and as a comedian (in 2019, she participated in the St. Paul troupe Funny Asian Women Kollective or FAWK). I played Marina’s free, funny solo game Secrets Agent, featuring the most charming and descriptive self-sung theme song this side of Fishing With John. Playing Secrets Agent came as an especially fun surprise, since I tend not to think of Analgesic as makers of especially comedic games. “I hear about Secrets Agent being enjoyed in classroom settings and by people who don’t play many games and that always makes me happy," Kittaka says. “Even though Analgesic games often have an overarchingly melancholic atmosphere, I actually consider humour to be a really important part of our style! Humour is incredibly human and connective and in real life it often expands into unexpected emotional spaces. Melos’s humor is more dry or biting, while mine tends to be based more in weird thoughts, bits, or wordplay.” As my Gaymer Gals Are Go! Co-host Kelly Marine pointed out when we featured Kittaka with Sephonie on our show, playful little touches pop out, such as the descriptions of each option in the menus. This was much appreciated in the accessibility menus since, as Kelly has told me before, some git gud-style games literally make fun of the player for wanting to choose such options. And speaking of accessibility, I commended Analgesic for their strong commitment to making their games for as many players as possible. Still, Han-Tani points out, though video games are for everyone, not every game can be for everyone - and that’s actually alright. “Any base game design decisions are inherently exclusive - even outside of things like the English language and access to hardware, e.g. Sephonie requires the ability to navigate 3D space,” he explains. “We can include a wide variety of ways to tweak that experience, but inevitably we can’t cover every possible player. While that feels frustrating, I think that’s okay. We do due diligence based on our capacity, and there’s no need to bear the pressure of perfection as a small team - especially when companies with far more resources get away with, and are praised for, inaccessible experiences. I tend to think more players should keep this in mind when giving feedback to small teams.” “If you keep accessibility in mind from the beginning, then you can reduce the amount of difficult-to-implement retroactive changes,” Kittaka adds. “I also think there’s a lot of potential for game design that inherently centers different bodies and minds and I’d like to learn more about disabled creators who are doing this work.” I’ve just read chunks of what I’m beginning to consider Kittaka’s solo magnum opus, 2018’s New Private Window. I think of it as something of a precursor to our friend Carta Monir’s own magnum opus, 2019’s Napkin. Both pay-what-you-can works follow young trans women of color coming into their own, reshaping their personal histories, identities, and relationships to their own genders and sexualities, and both feature text and informal, yet carefully-composed, photography. I had to ask Kittaka: what was it like to release such a transformative, richly personal work? What was it like working on it, sifting through those old photos, old relationships, those old permutations of identity? “Napkin is really beautiful. I think as general visibility increases there’s perhaps a pressure on trans artists to make themselves legible through certain canonized stories,” she says. “So one thing I appreciate about Napkin and New Private Window is that they’re both formally playful (e.g. Napkin’s comment cards and NPW’s web browser stuff). There’s this sense of not really wanting to take anything for granted—not wanting to create by pouring ’trans content’ into a default container.” As a white woman whose maternal grandfather was Colombian and Chinese, I’m interested by stories of diaspora and mixed-race characters, and Analgesic’s Asian protagonists present themselves as among the most complexly-crafted heroes in gaming. I asked Han-Tani - the lead writer on Sephonie (where usually Kittaka has been the lead writer on Analgesic’s games) - about his process of writing mixed-race characters. “Part of writing as mixed-race for me, is to illustrate the differences within a group of peoples. Especially against the narrative of a country’s marketing of e.g. ‘What it means to be Japanese,’ or outsiders’ perception of Japanese people,” he says. “These things usually mean a lot less than what an individual person is actually doing with their life. One thing that hopefully I got at a little was, how, in the case of Japan or Taiwan, the experience of growing up bilingual separates you from the population who remains monolingual.” This is, Han-Tani explains, due to the media you can consume, people you can meet and places you can go - especially in the case of learning English, which Han-Tani thinks is now going to remain the dominant language of the world for the rest of human history. “In some ways,” he adds, “Sephonie is an illustration of a financially privileged class of Japanese/Taiwanese who know English. The degree of the separation from a monolingual society that bilingualism brings varies from person to person (and the languages in question). I also think there are parallels between being mixed race and bilingual, since you’re existing between the borders of two or more groups, navigating for yourself what that means.” Liminal spaces tend not to be where one most likely intended to go, but in 2022, turns out they may be the best place for video game makers to be. In 2020 alone Kittaka created the free-to-use blogging tool Zonelets, as well as writing a seminal blog post entitled Divest from the Video Games Industry!. In February 2018 Han-Tani released a 3D meditational adventure “about identity, race, and nationality” - and, I would add, family and memory - called All Of Asias, free on Steam and Itch.io. His thoughts on the state of the commercial video game industry may, or may not, surprise you. “A lot of games coming out nowadays - the vast majority of AAA and much of commercial indie - is just not very interesting, often being middling both from a thematic depth standpoint, but even from a game design standpoint, games tend to stick to trends or haphazardly borrow from older games,” he says. “Much of design is being driven by metrics - engagement and increasing screen time, but still being passed off as trying to aspire to be ‘art’… it’s all very absurd to watch from the sidelines. “That being said, as I get older I try not to be part of the commercial developer scene as much and focus on making friends more on the outskirts of games, or not even related to games at all! It’s good to have perspective.” It’s good to have perspective, Han-Tani of Analgesic Productions tells me, on games, work, and life.