“Oh yes, of course! Certainly it was! Moreover, due to the conditions in which we constructed this game, it was a miracle that we released it. But I wouldn’t say it’s the game we wanted to release.” Even now, over a year after Pathologic 2’s release, Nikolay Dybowski and Ivan Slovtsov have differing opinions about the surrealistic survival game they played leading roles in making. In fact, they’re still unpacking their thoughts about what they created, particularly in light of the changes they made after launch to its difficulty setting, a system which lies at the centre of a game which sets out to express the struggle in death and life.

Coincidently, the day I speak to Dybowski and Slovtsov is the exact first anniversary of the day they published a post on Steam called On Difficulty. Just four days before, they’d launched Pathologic 2 to sweeping criticism that it was far too hard, an issue shared by Brendan (RPS in peace) when he reviewed it for this very organ, and in the post they explained how they were planning to address it. Pathologic 2 can, after all, feel punishing. Across its plague-stricken town you’ll come across characters who need your help, but you can’t save them all in the time you have, especially since you have to invest so many of the scarce resources you find in simply keeping yourself alive against ever-encroaching hunger, thirst and fatigue. And when you die, some of your core stats are going to diminish, making you weaker for your next attempt. “It started for me as an experiment, because every Ice-Pick Lodge game is sort of an experiment,” says Dybowski, who founded the studio and conceived the original Pathologic, which came out in Russia in 2005 and forms the raw, beating heart of its sequel. “We wanted very much to try to offer our players a strange narrative game where they aren’t told what to do,” he continues. “No quest log, no quest-givers to tell you your mission and next goal and purpose, and that the player is the one who must form this goal or purpose it on their own. It was a daring experiment, and that experiment did fail. Yes, Ivan, I think it did.”

And that’s partly because the Pathologic 2 that eventually came out does have quest-givers and you do have a clear purpose: to find out who killed your father and the cause of the plague. The game evolved greatly over the course of its long development, much down to Slovtsov, who brought with him a more practical sensibility, one which would make the game play closer to contemporary conventions. “It had a really troubled development cycle,” says Slovtsov. “The loss of funding from the investor we hoped for, three years of looking for money to finish the game while making demos to attract publishers and media, and then we signed with Tiny Build and the game came out. But that was five years of struggle and I think that shaped the game, which in the end became about struggle.” So when they designed Pathologic 2 to be difficult, Ice-Pick intended it to pose stern - and meaningful - choices over what you’ll strive for, and what you’ll leave behind. The challenge - the struggle - was an indelible part of the game.

“But you can’t overcome struggle if there’s nothing to overcome,” says Slovtsov. “At the high level, the difficulty of Pathologic was there because it was the exact experience we wanted to give. It’s not a balance issue. ‘Why is your balance so f’d up?’ some people said in Steam and media reviews. It wasn’t an error, it was a goal to create a game with this kind of experience.” You can forgive the team for hoping this concept would work better for players than it did. Since the release of the original Pathologic in 2005, game design had swung towards the difficult choices, permadeath and acceptance of loss found in Rogue-likes and, dare we say it, Dark Souls. “It’s not like we wanted to make a Dark Souls-like game. It’s a completely different genre,” says Slovtsov. “But many people in the studio are fans of the series and what Dark Souls did with giving you stakes in the game gave us the feeling that yeah, people should be ready for this by now.”

The key misstep, then, is that Ice-Pick didn’t realise they’d gotten it wrong as they tested the game. Slovtsov says they extensively play-tested Pathologic 2, anxious to prevent the high difficulty, particularly the way the game reduces your stats when you die, from blocking progress. “We wanted you to roll with the punches and to push forward; we wanted the game to be about struggle but not about giving up.” But the playtesters mostly came from Pathologic’s existing audience. They already knew - and loved - what kind of a game they’d be playing. They expected it to set out to punish and intimidate them as a way of underscoring its themes. “Basically my most beloved idea behind Pathologic 2 was that it is a game about limitations,” explains Dybowski. Its key theme is that humanity is chained by our perception of what we’re capable; that we have the capacity to do so much more. So, as Pathologic’s characters helplessly face a terrible and deadly epidemic, we see how they apportion blame and wring their hands rather than save themselves. “Actually, these are the limits of our consciousness and minds, which stop us earlier than we’d otherwise from doing something, and this really brings us down. It makes us more animals than people,” says Dybowski. “That’s why death was suggested as a basic limit which actually exists more in our mind than in real life.”

It was late in the game’s development - the final year - when they began to think about how to implement this idea. They’d watched the acclaim with which Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice was received, a game which claimed that if you allowed Senua’s disease, dark rot, to progress up her arm and infect her head, it would delete your save files. “But it wasn’t true!” says Slovtsov. “It wasn’t true, yes. Very soon, this scary image stopped working because people knew it was just an atmospheric feature. We decided to design something…” “Something that actually had consequences.” “Yes. Well, consequences in game mechanics.” And so Pathologic 2 can permanently limit pretty much any numerical characteristic when you die. Dybowski then established the structure in which the game plays out: you start in the theatre that stands in the middle of the town, talking to a theatre director called Mark Immortell (Dybowski, whose parents were Soviet-era theatre directors, holds a deep fascination for theatre). This sequence is intended to frame each run as a chance to perform the role of the main character, the Haruspex, just a little more successfully than the last.

“You are not a single person, you are a series of persons, attempts,” says Dybowski. “Ivan, don’t tell me about BioShock, please. It’s a shame, but I didn’t play BioShock Infinite. Ivan told me, ‘Nikolay, play the game! You must do it! Come sit by me, I will show you the final scene!’ And I said no, I don’t want to do it.” “But if you really think about most of the penalties for death, they didn’t change how you play the game much, but they sound super scary,” says Slovtsov. “That’s what we wanted, for death to be scary. But maybe we scared people too much, because I saw reviews saying, ‘Nope, I’m not playing this, this is bullshit. This game is unbeatable.’” Ice-Pick are not proponents of ‘gitting gud’. And while they stand by Pathologic 2’s difficulty design, they don’t believe it’s sacrosanct, or that players misunderstood what they were setting out to achieve.

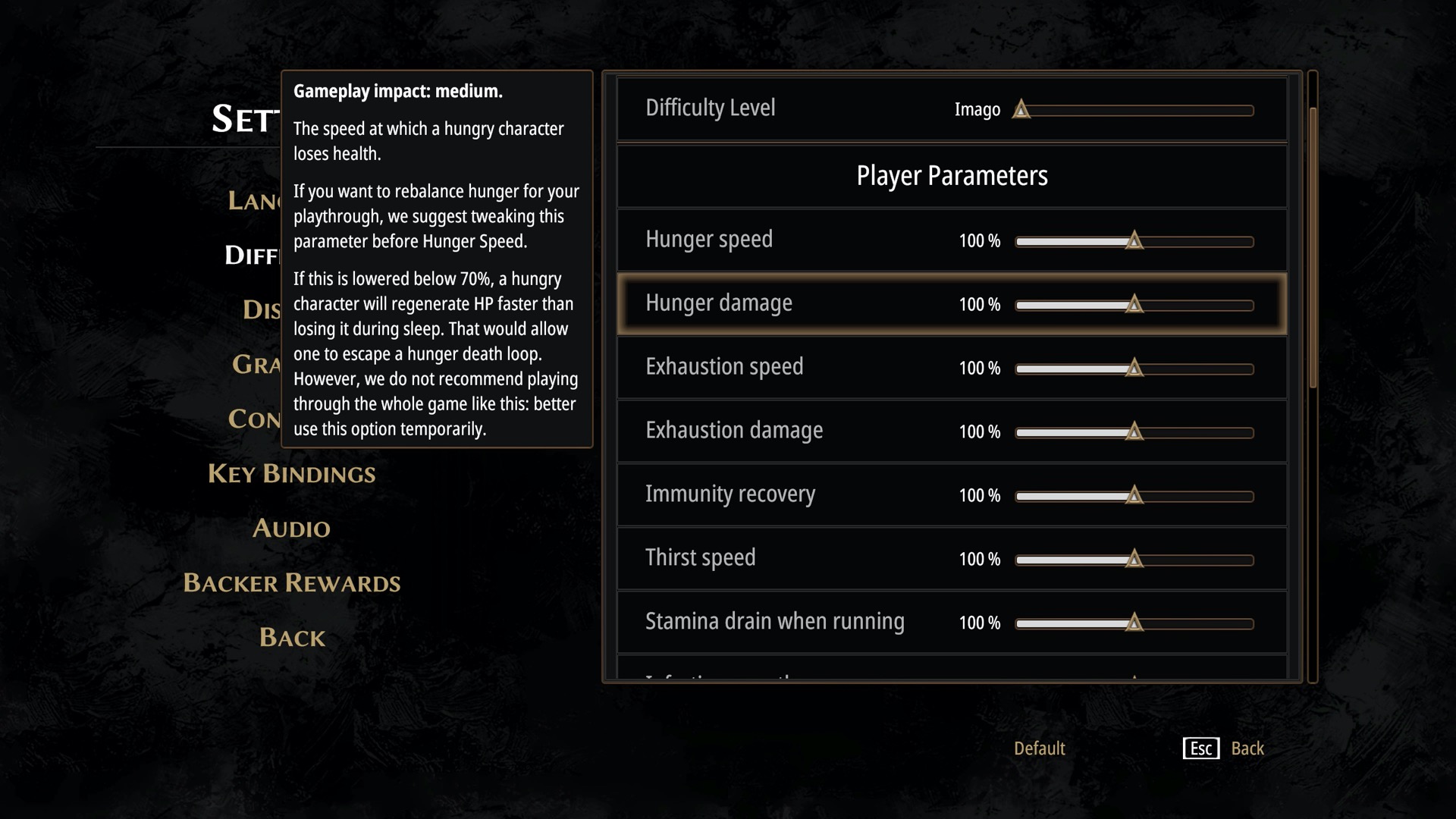

“We really wanted everyone to have this experience we were talking about,” says Slovtsov. “It’s not this elitist gateway to some kind of ascension to being a better human. We couldn’t do anything for people who wanted other kinds of experiences, but we could help people who wanted to experience the game we made but they physically couldn’t play further because they’d keep dying on day two.” The studio went much further than simply setting up Easy, Medium and Hard difficulty levels. They opened up sliders for a vast array of settings, available at any time during play and inspired by the way strategy games like Civilization let you fine-tune scenarios. Each slider details what it does and - crucially - how it relates to Ice-Pick’s intention and how it might help you.

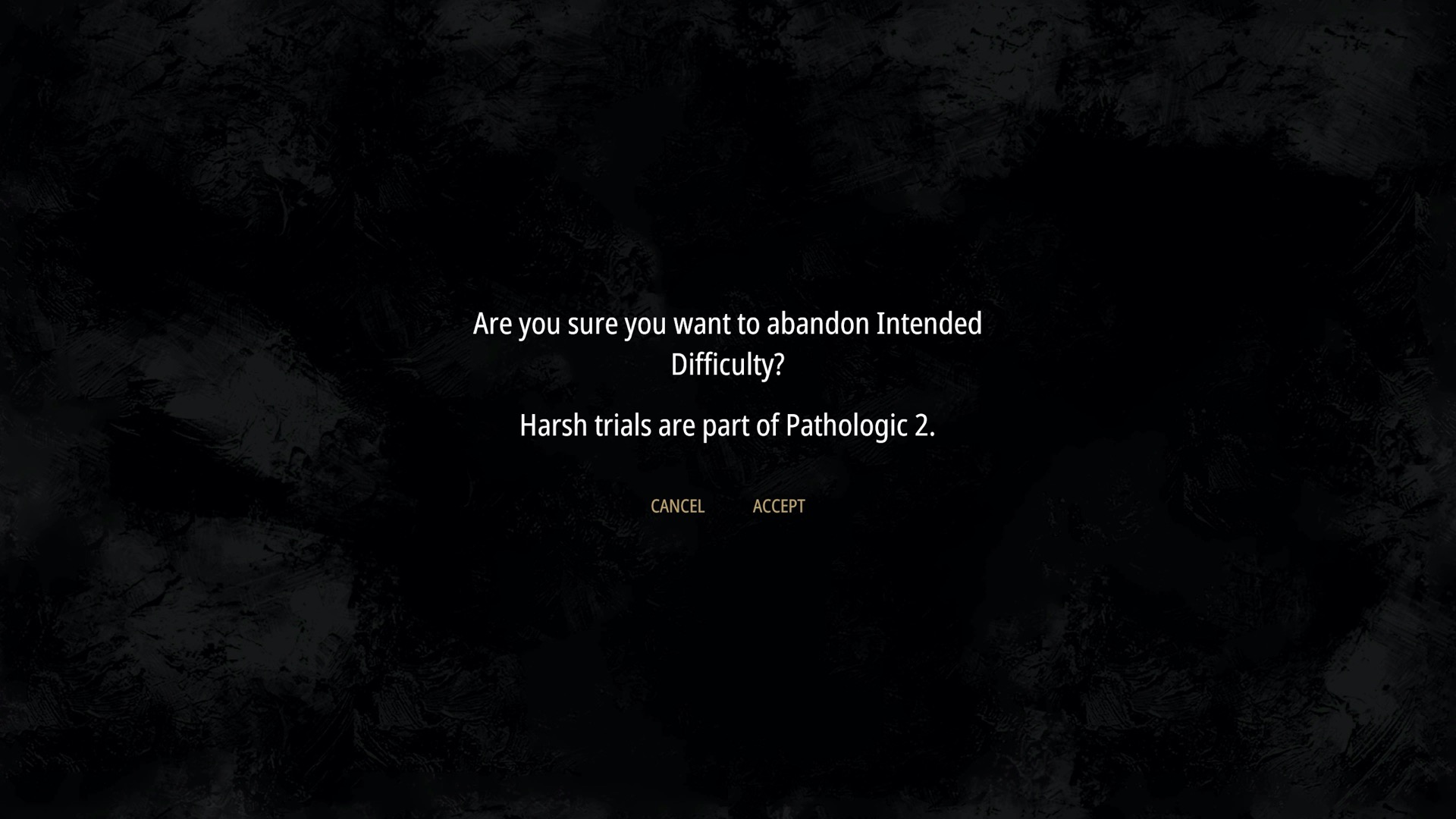

There’s Infection Chance (“how can you fight the plague if you’ve never experienced it?”), Clothes Wear-and-Tear, Damage Received; there are 15 sliders in total, along with three presets, in which the highest is Intended Difficulty, the middle level, Cocoon, is described as hard, and the lowest, Larva, is stated as medium difficulty. The tone of the language around all these settings still very much encourages you to stick with the original design. When you uncheck the “Intended Difficulty” option, you get this screen:

“One of the hardest things to do for the difficulty sliders update was the text! The wording changed many many times,” says Slovtsov. “We wanted to say, look you’re a grown-up, we trust you to make the best choices for yourself. We just want to inform you about what everything is so you make informed choices, and not just random ones.” And so the patch went live and Pathologic 2’s Steam review score improved from the 80% it had on release to today’s 92%. Play statistics also suggested the change helped: after release, only 20% of players got the achievement for completing day one. Now it’s 44%. User review scores aside, it’s hard to say that the difficulty patch explicitly turned around Pathologic 2’s fortunes, fortunes which over the past year have put into question Ice-Pick’s crowdfunding promise to add the two other characters - the Batchelor and Changeling - who were established in the original game. But they’ve now re-committed to adding them as DLC, because they gave their word and because for Dybowski they’re necessary for Pathologic 2’s story. It’s also hard to say whether, in a creative sense, putting the difficulty design into players hands truly addressed the issue, since the game does so much to tell you that the original scheme is the ideal way to play. But whichever way you look at it, Pathologic 2 is absolutely a game about struggle: of the human condition, of the player, of the developer. “Nikolay often talks about it like this huge - well, not a compromise, but as if we really changed the game to fit the zeitgeist. But I believe the game is still very true to the original. It’s just more modernised and not in a bad way, if you know what I mean.” “Well actually, Ivan, I agree with you, because we did our best to do so.”