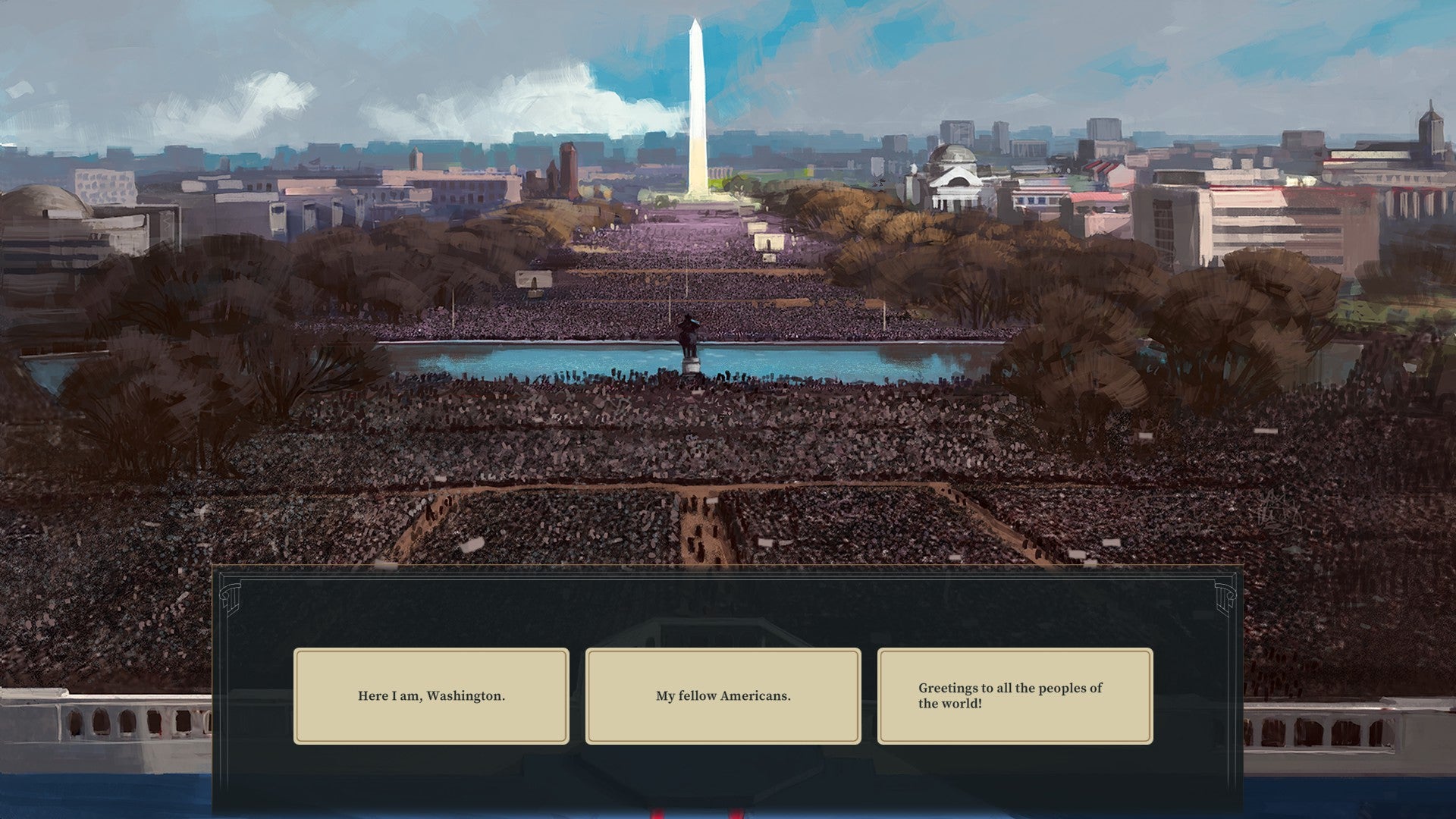

It has, however, got me considering what exactly “political strategy game” means. The first interesting thing about This Is The President is that your goal isn’t to get re-elected or to run the country well. Your first act is a victory speech that you build sentence by sentence from a handful of slightly branching options, none of which you have any context for. What seems like a flaw is then revealed as subtext when your wife pulls you aside and confirms your true motivations: to secure immunity from prosecution by passing an amendment to the Constitution at any cost. You are a massive crook, even by presidential standards, and it doesn’t matter what you promise or achieve or leave behind for everyone else to deal with, as long as you get that amendment. If you still weren’t sure how serious the game was, it’s not long before you’re invited to a musical by an old acquaintance. The cutscene that plays for this was such a bewildering delight that I’m tempted to recommend the game just so you can experience it for yourself. Suffice to say that the dialogue options afterwards include dismissing the whole thing as delusional, and confessing to your wife that the plot of the play is a true story, retroactively giving your character a scandalous past that you can attempt to cover up by, among other possibilities, having your IT guy blow up the playwright with a drone. This is not a game to be taken entirely at face value. And against my assumptions, it works. It’s refreshing to see a work about American politicians that doesn’t treat them with reverence, but as unremarkable figures in an innately corrupt system much like the sadly never-followed Shape Of America. The plot has enough levity to keep you from agonising over decisions. Especially once it tells you, a little too far in, that you can replay a month at any time. This isn’t as useful as a full save function, but it’s adequate for keeping the fear of screwing your run up with one misclick or poor decision. It keeps the story and your thoughts moving, always focused on that single, very tangible goal. Each month you’re faced with a number of events, and must address them through dialogue choices for most of the plot-central ones, and by ordering your personal staff to carry out the tasks you think will help. Each staff-based event asks you to choose one or more staff to bring along, and they’ll suggest possible solutions that suit their expertise and personality. Much like Hidden Agenda, you have to rely on your staff to offer proposals, so my hacker guy was instrumental in finding a missing person from scooped data. But when it came to creating a diversion in public, the best he could come up with was “present a free remote lecture on data analysis nearby”, while the lawyer, excellent at matters of procedure and paperwork, suggested threatening a load of homeless people with a lawsuit. Once an event starts, you can often draft in an extra person for more relevant expertise. It’s a good way to mitigate that common problem in games where you’re not given enough information to judge what to commit to until you’re ambushed by a surprise twist, or one of your people lets you down. It also sells the setting, as you can easily imagine the hurried phone calls and angry taxi rides and Malcolm Tucker’s prancing running about. There’s a cost to this though, which varies between characters. My PR star, corrupt and avaricious, nonetheless knows her value and demands a raise for it, while another will suggest you’ll owe them one down the line. Drafting them last minute stresses them out too, more than if you’d called them to begin with but never used them. Stress is a core system in fact, as anything your staff do wears them down, limiting what you can achieve in any month. It goes down when they get holidays or expensive perks, and up in varying amounts when you lean on them in events. There’s not a direct correlation between the stress cost of an action and its efficacy, making it a game of judgement and reasoning rather than number-crunching. Stress can go up or down passively depending on who you’ve appointed to each formal office, which will also change income or public opinion over time, again depending on the individual. Money is important but your main resource is your staff, and half the game is in the balance between keeping them busy, keeping them rested and ready to deal with problems, and hopefully only occasionally letting them burn out. Staff even react to burnout in different ways. One character didn’t ask for anything when I drafted him into an event, but did say that he felt like the rest of the team didn’t like him and asked if I was sure I wanted him to come. Where my crooked press secretary can basically be paid to burn out, this guy instead asks for nothing, but makes comments that make me worry about his mental wellbeing. Of course, mechanically, it would make sense to squeeze him more because his extra work is “free”. But that’s where you hit that line, isn’t it? It’s a line that the utterly brilliant Suzerain lived on, between simulation and story. And that’s where a character moment in a narrative-heavy, low-simulation game illustrates something that a great many polsims neglect. People. This Is The President is driven far more by narrative than by simulation, even compared to Suzerain, which was more interactive fiction than a strategy game. But in some ways I was thinking more strategically than in both that, and in a very mechanical simulation like The Political Process. In the former I was trying to do the right thing and trust the right people. In the latter, excellent as it is, I was often thinking about numbers. The same was true of ministers in Shadow President, or Democracy. Whatever their window dressing, when political games focus so heavily on systems and simulation, the people in them become mere machines you can mathematically draw maximum efficiency from. While they, or, say, Crusader Kings 3, can generate narratives, those tend to come after the fact, and don’t really serve the strategic element, nor are served by it. This Is The President, by contrast, is a strategy game about managing staff as characters in service of a story. That’s something any political game should surely centre as much as raw data. Politics is, by its very nature, as unpredictable as life itself. Sure, the broad strokes remain the same across most cultures and eras. There are patterns. But the details aren’t the same. And a life in politics is surely little more than a 24/7 barrage of details. Making a strategic challenge out of that is the true problem a political game designer has to address, not covering more thematic ground or modelling more systems. The cost in this case is that, even more than Suzerain’s many secrets and interrelated subplots and side events, This Is The President can only provide so many permutations of its one main plot. You can twist that plot here and there in dialogues, filling in your back story a little. There’s a hint of something like 80 Days in that it sort of encourages you to go for options that are obviously a terrible idea just to see what happens. Or perhaps it compares better, weirdly, to Skyward Collapse, a game that I only enjoyed when I realised you weren’t supposed to be cautious and sensible, but to gleefully escalate hard and often then try to deal with the spiralling consequences. But you’re still the same crook. Playing that explicitly crooked person is oddly freeing, as the game never assumes your president’s actions reflect anything about you as a person. Anything immoral or inconsistent is just a means to an end. Be it the safe route of gathering enough money and material to bribe and blackmail your legislation through, or agreeing to every radical change in a bid to pressure the Supreme Court through overwhelming public opinion. Or do you even want to have a change of heart, and make an effort to be an actually good head of state? Your average Prez or PM pursues high office for various combinations of greed, sociopathy, and megalomania, and this one wants nothing more than a get out of jail free card. But since you have no other agenda and no interest in remaining in office, it’s possible to accept your looming arrest and do some good before you go. I was willing to hit a lot of big targets hard for the gain in public support, and the sheer novelty of a president not afraid to call the NRA evil mass murdering bastards. But also totally willing to solicit an occasional kickback or invest in an underhanded scheme or twelve for profit. Got to get that bribe money. Eyes on the prize and all that. I’ve enjoyed This Is The President. It’s an edge case as far as strategy goes, but it’s got me optimistic for where political strategy games might be going over the next few years. For most of my life it’s been slim pickings, with a very dry, spreadsheet-y feel, and a disproportionate focus on elections. I think there’s plenty of room for more imaginative fare, with more exploration of storytelling, and of government as a dramatic interplay of the personal and political. And if nothing else, it’s quite an achievement to portray an outright criminal in office in the present day without just feeling depressingly accurate.